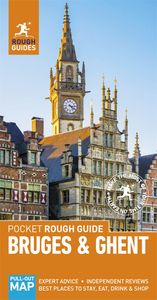

The Burg

From the east side of the Markt, Breidelstraat leads through to the city’s other main square, the Burg, named after the fortress built here by the first count of Flanders, Baldwin Iron Arm, in the ninth century. The fortress disappeared centuries ago, but the Burg long remained the centre of political and ecclesiastical power with the Stadhuis (which has survived) on one side and St-Donaaskathedraal (which hasn’t) on the other. The French army destroyed the cathedral in 1799 and although the foundations were laid bare in the 1950s, they were promptly re-interred – they lie in front of and underneath the Crowne Plaza Hotel.

The southern half of the Burg is fringed by the city’s finest group of buildings, beginning on the right with the Heilig Bloed Basiliek (Basilica of the Holy Blood) named after the holy relic that found its way here in the Middle Ages. The church divides into two parts. Tucked away in the corner, the lower chapel is a shadowy, crypt-like affair, originally built at the beginning of the twelfth century to shelter another relic, that of St Basil, one of the great figures of the early Greek Church. The chapel’s heavy and simple Romanesque lines are decorated with just one relief, carved above an interior doorway and showing the baptism of Basil in which a strange giant bird, representing the Holy Spirit, plunges into a pool of water.

Next door, approached up a wide, low-vaulted curving staircase, the upper chapel was built a few years later, but has been renovated so frequently that it’s impossible to make out the original structure; it also suffers from excessively rich nineteenth-century decoration. The building may be disappointing, but the large silver tabernacle that holds the rock-crystal phial of the Holy Blood is simply magnificent, being the gift of Albert and Isabella of Spain in 1611. One of the holiest relics in medieval Europe, the phial of the Holy Blood purports to contain a few drops of blood and water washed from the body of Christ by Joseph of Arimathea. Local legend asserts that it was the gift of Diederik d’Alsace, a Flemish knight who distinguished himself by his bravery during the Second Crusade and was given the phial by a grateful patriarch of Jerusalem in 1150. It is, however, rather more likely that the relic was acquired during the sacking of Constantinople in 1204, when the Crusaders simply ignored their collective job description and robbed and slaughtered the Byzantines instead – hence the historical invention. Whatever the truth, after several weeks in Bruges, the relic was found to be dry, but thereafter it proceeded to liquefy every Friday at 6pm until 1325, a miracle attested to by all sorts of church dignitaries, including Pope Clement V.

The phial of the Holy Blood is still venerated and, despite modern scepticism, reverence for it remains strong. It’s sometimes available for visitors to touch under the supervision of a priest inside the chapel, and on Ascension Day (mid-May). it’s carried through the town centre in a colourful but solemn procession, the Heilig-Bloedprocessie, a popular event for which grandstand tickets are sold at the main tourist office from March 1.

The shrine that holds the phial during the procession is displayed in the tiny Schatkamer, next to the upper chapel. Dating to 1617, it’s a superb piece of work, the gold and silver superstructure encrusted with jewels and decorated with tiny religious figures. The treasury also contains an incidental collection of ecclesiastical bric-a-brac plus a handful of old paintings. Look out also, above the treasury door, for the faded strands of a locally woven seventeenth-century tapestry depicting St Augustine’s funeral, the sea of helmeted heads, torches and pikes that surround the monks and abbots very much a Catholic view of a muscular State supporting a holy Church.

The Groeninge Museum

The Groeninge Museum possesses one of the world’s finest samples of early Flemish paintings, from Jan van Eyck through to Hieronymus Bosch and Jan Provoost. These paintings make up the kernel of the museum’s permanent collection, but there are later (albeit lesser) pieces on display too, reaching into the twentieth century, with works by the likes of Constant Permeke and Paul Delvaux.

Arguably the greatest of the early Flemish masters, Jan van Eyck (1385–1441) lived and worked in Bruges from 1430 until his death eleven years later. He was a key figure in the development of oil painting, modulating its tones to create paintings of extraordinary clarity and realism. The Groeninge has two gorgeous examples of his work, beginning with the miniature portrait of his wife, Margareta van Eyck, painted in 1439 and bearing his motto, “als ich can” (the best I can do). The painting is very much a private picture and one that had no commercial value, marking a small step away from the sponsored art – and religious preoccupations – of previous Flemish artists. The second Eyck painting is the remarkable Madonna and Child with Canon George van der Paele, a glowing and richly symbolic work with three figures surrounding the Madonna: the kneeling canon, St George (his patron saint) and St Donatian, to whom he is being presented. St George doffs his helmet to salute the infant Christ and speaks by means of the Hebrew word “Adonai” (Lord) inscribed on his chin strap, while Jesus replies through the green parrot in his left hand: folklore asserted that this type of parrot was fond of saying “Ave”, the Latin for welcome. The canon’s face is exquisitely executed, down to the sagging jowls and the bulging blood vessels at his temple, while the glasses and book in his hand add to his air of deep contemplation. Audaciously, van Eyck has broken with tradition by painting the canon among the saints rather than as a lesser figure – a distinct nod to the humanism that was gathering pace in contemporary Bruges.

The Groeninge possesses two fine and roughly contemporaneous copies of paintings by Rogier van der Weyden (1399–1464), one-time official city painter to Brussels. The first is a tiny Portrait of Philip the Good, in which the pallor of the duke’s aquiline features, along with the brightness of his hatpin and chain of office, are skilfully balanced by the sombre cloak and hat. The second and much larger painting, St Luke painting the Portrait of Our Lady, is a rendering of a popular if highly improbable legend that Luke painted Mary – thereby becoming the patron saint of painters. The painting is notable for the detail of its Flemish background and the cheeky-chappie smile of the baby Christ.

Also noteworthy is the spookily stark Surrealism of Paul Delvaux’s (1897–1994) Serenity. One of the most interesting of Belgium’s modern artists, Delvaux started out as an Expressionist but came to – and stayed with – Surrealism in the 1930s. This painting is a classic example of his oeuvre and, if it whets your artistic appetite, you might consider visiting Delvaux’s old home, in St-Idesbald, which has been turned into a museum with a comprehensive selection of his paintings (see The Atlantikwall).

The Groeninge also owns a couple of minor oils and a number of etchings and drawings by James Ensor (1860–1949), one of Belgium’s most innovative painters, and Magritte’s (1898–1967) characteristically unnerving The Assault; for more on Magritte

The Hospitaalmuseum and the Memling Collection

Opposite the entrance to the Onze Lieve Vrouwekerk is St-Janshospitaal, a sprawling complex that sheltered the sick of mind and body until well into the nineteenth century. The oldest part – at the front on Mariastraat, behind two church-like gable ends – has been turned into the slick Hospitaalmuseum, while the nineteenth-century annexe, reached along a narrow passageway on the north side of the museum, has been converted into a really rather tatty exhibition-cum-shopping centre called – rather confusingly – Oud St-Jan.

The Hospitaalmuseum divides into two, with one large section – in the former hospital ward – exploring the historical background to the hospital through documents, paintings and religious objets d’art. Highlights include a pair of sedan chairs used to carry the infirm to the hospital in emergencies, and Jan Beerblock’s The Wards of St Janshospitaal, a minutely detailed painting of the hospital ward as it was in the late eighteenth century, the patients tucked away in row upon row of tiny, cupboard-like beds. Other noteworthy paintings include an exquisite Deposition of Christ, a late fifteenth-century version of an original by Rogier van der Weyden, and a stylish, intimately observed diptych by Jan Provoost, with portraits of Christ and the donor – a friar - on the front and a skull on the back.

The old chapel inside the Hospitaalmuseum displays six wonderful paintings by Hans Memling (1433–1494). Born near Frankfurt, Memling spent most of his working life in Bruges, where Rogier van der Weyden instructed him. He adopted much of his tutor’s style and stuck to the detailed symbolism of his contemporaries, but his painterly manner was distinctly restrained, often pious and grave. Graceful and warmly coloured, his figures also had a velvet-like quality that greatly appealed to the city’s burghers, whose enthusiasm made Memling a rich man – in 1480 he was listed among the town’s major moneylenders.

Of the six works on display, the most unusual is the Reliquary of St Ursula, comprising a miniature wooden Gothic church painted with the story of St Ursula. Memling condensed the legend into six panels with Ursula and her ten companions landing at Cologne and Basle before reaching Rome at the end of their pilgrimage. Things go badly wrong on the way back: they leave Basle in good order, but are then – in the last two panels – massacred by Huns as they pass through Germany. Memling had a religious point to make, but today it’s the mass of incidental detail that makes the reliquary so enchanting, providing an intriguing evocation of the late medieval world. Equally delightful is the Mystical Marriage of St Catherine, the middle panel of a large triptych depicting St Catherine, who represents contemplation, receiving a ring from the baby Jesus to seal their spiritual union. The complementary side panels depict the beheading of St John the Baptist and a visionary St John writing the Book of Revelation on the bare and rocky island of Patmos. Again, it’s the detail that impresses: between the inner and outer rainbows above St John, for instance, the prophets play music on tiny instruments – look closely and you’ll spy a lute, a flute, a harp and a hurdy-gurdy. Across the chapel are two more Memling triptychs, a Lamentation and an Adoration of the Magi, in which there’s a gentle nervousness in the approach of the Magi, here shown as the kings of Spain, Arabia and Ethiopia.

Memling’s skill as a portraitist is demonstrated to exquisite effect in his Portrait of a Young Woman, where the richly dressed subject stares dreamily into the middle distance, her hands – in a superb optical illusion – seeming to clasp the picture frame. The lighting is subtle and sensuous, with the woman set against a dark background, her gauze veil dappling the side of her face. A high forehead was then considered a sign of great womanly beauty, so her hair is pulled right back and was probably plucked – as are her eyebrows. There’s no knowing who the woman was, but in the seventeenth century her fancy headgear convinced observers that she was one of the legendary Persian sibyls who predicted Christ’s birth; so convinced were they that they added the cartouche in the top left-hand corner, describing her as Sibylla Sambetha – and the painting is often referred to by this name.

The sixth and final painting, the Virgin and Martin van Nieuwenhove diptych, is exhibited in the adjoining side chapel. Here, the eponymous merchant has the flush of youth and a hint of arrogance: his lips pout, his hair cascades down to his shoulders and he is dressed in the most fashionable of doublets – by the middle of the 1480s, when the portrait was commissioned, no Bruges merchant wanted to appear too pious. Opposite, the Virgin gets the full stereotypical treatment from the oval face and the almond-shaped eyes through to full cheeks, thin nose and bunched lower lip.

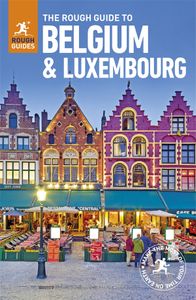

The Markt

At the heart of Bruges is the Markt, an airy open space edged on three sides by rows of gabled buildings and with horse-drawn buggies clattering over the cobbles. The burghers of nineteenth-century Bruges were keen to put something suitably civic in the middle of the square and the result was the conspicuous monument to the leaders of the Bruges Matins, Pieter de Coninck, of the guild of weavers, and Jan Breydel, dean of the guild of butchers. Standing close together, they clutch the hilt of the same sword, their faces turned to the south in slightly absurd poses of heroic determination.

The biscuit-tin buildings flanking most of the Markt form a charming architectural chorus, their mellow ruddy-brown brick shaped into a long string of pointed gables, each gable of which is compatible with but slightly different from its neighbour. Most are late nineteenth- or even twentieth-century re-creations – or re-inventions – of older buildings, though the old post office, which hogs the east side of the square, is a thunderous neo-Gothic edifice that refuses to camouflage its modern construction. The Craenenburg Café, on the corner of St Amandsstraat at Markt 16, occupies a modern building too, but it marks the site of the eponymous medieval mansion in which the guildsmen of Bruges imprisoned the Habsburg heir, Archduke Maximilian, for three months in 1488. The reason for their difference of opinion was the archduke’s efforts to limit the city’s privileges, but whatever the justice of their cause, the guildsmen made a big mistake. Maximilian made all sorts of promises to escape their clutches, but a few weeks after his release his father, the Emperor Frederick III, turned up with an army to take imperial revenge. Maximilian became emperor in 1493 and he never forgave Bruges, doing his considerable best to push trade north to its great rival, Antwerp.