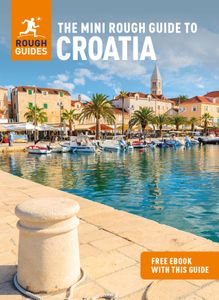

Gradec

Gradec (or more colloquially “Grič”) is the oldest and most atmospheric part of Zagreb, a leafy, tranquil area of tiny streets, small squares and Baroque palaces, whose mottled brown roofs peek out from the hill. The most leisurely approach is to take the funicular (uspinjača), which ascends from Tomićeva, an alleyway about 200m west of Trg bana Jelačića; alternatively, wander up the gentle gradient of Radićeva towards the Kamenita vrata, or “stone gate”, which originally formed the main eastern entrance to the town. Inside Kamenita vrata – actually more of a long curving tunnel than a gate – lies one of Zagreb’s most popular shrines, a simple sixteenth-century statue of the Virgin in a grille-covered niche. Miraculous powers have been attributed to the statue, largely on account of its surviving a fire in 1731 – a couple of benches inside the gate accommodate passing city folk eager to offer a quick prayer.

Museum of Broken Relationships

For a voyage into the more tumescent recesses of the human psyche then there are few better starting points than Zagreb’s Museum of Broken Relationships (Muzej prekinutih veza), the celebrated art installation that became a permanently grounded museum in 2010. It started out as an exhibit at the Zagreb Salon of 2006, at which co-creators Olinka Vištica and Dražen Grubišić (themselves a former item) displayed a collection of objects connected with all aspects of break-up, many of which were donated by friends with a story to tell. The exhibit struck an instant chord with the public, and became an international travelling exhibition, adding to its collection as more and more people donated meaningful mementoes.

Now located on the ground floor of Gradec’s Kulmer Palace, it’s a compelling and unique museum of wistful memory and raw emotion. Each exhibit is accompanied by a text explaining why it was significant to the donor – some are touching, others quite kinky, and a few belong to the obsessive world of a David Lynch movie. The broken relationships in question aren’t always what one expects; one member of the public donated the hands of his favourite mannequin, another an oil painting of a politician who failed to deliver. Among the most poignant exhibits is a comic book purchased after a particular break-up – because the ex-boyfriend in question had departed leaving nothing to be remembered by.

It is also one of the few Zagreb museums that has a genuinely cute café and a well-patronized shop: Bad Memory Eraser pencil rubbers are among the big sellers.

Zagreb's Lower Town

South of the Upper Town, the modern Lower Town (Donji grad) is a bit of a sprawl, with grey office blocks and apartment buildings surrounding the occasional example of imposing Habsburg-era architecture. Breaking the urban uniformity is a series of interconnected garden squares, laid out from the 1870s onwards, which gives the downtown area a U-shaped succession of promenading areas and parks. Known as Lenuci’s Horseshoe (Lenucijeva podkova) after Milan Lenuci, the city planner responsible for its layout, this was a deliberate attempt to give Zagreb a distinctive urban identity, providing it with public spaces bordered by the set-piece institutions – galleries, museums and theatres – that it was thought every modern city should have. The horseshoe was never finished, though, and it’s unlikely you’ll follow the full U-shaped itinerary intended by Lenuci. The first of the horseshoe’s two main series of squares starts with Trg Nikole Šubića Zrinskog – usually referred to as Zrinjevac – which begins a block south of Trg bana Jelačića; to the west of Zrinjevac is the second line of squares, culminating with Trg maršala Tita. To the south are the Botanical Gardens, which were intended to provide the final green link between the two arms of the horseshoe, but didn’t quite manage it: several characterless downtown blocks prevent it from joining Tomislavov trg to the east.

Nikola Tesla (1856–1943)

Born the son of a Serbian Orthodox priest in the village of Smiljan, just outside Gospić, Nikola Tesla went on to become the Leonardo da Vinci of the electronic age. He studied in Graz and Prague before working for telephone companies in Budapest and Paris, and in 1884 emigrated to the US where he found work with Thomas Edison – the pair allegedly fell out when Edison promised to reward Tesla with a US$50,000 bonus for improving his electricity generators, then failed to pay up.

After working for a time as a manual labourer, Tesla set up his own company and dedicated himself to the development of alternating current – a system that is now standard throughout the world. With financial support from American company Westinghouse, Tesla demonstrated his innovations at the Chicago World Fair in 1893, becoming an international celebrity in the process.

In 1899 Tesla moved to Colorado Springs, where he built an enormous high-frequency generator (the “Tesla Coil”), with which he hoped to transmit electric energy in huge waves around the earth. Photographs of Tesla’s tall, wiry figure using the coil to produce vast electronic discharges helped turn the inventor into one of the iconic figures of modern science.

Tesla also pioneered the development of long-range radio-wave transmissions, but failed to demonstrate his innovations publicly and was scooped by Giuglielmo Marconi, who successfully sent wireless messages across the Atlantic in 1902. The US patent office credited Marconi as the inventor of radio – a decision overturned in Tesla’s favour in 1943.

Official recognition eluded Tesla throughout his career. In 1915 the Nobel committee considered awarding their science prize jointly to Tesla and Thomas Edison, but changed their minds on discovering that the pair were too vain to share it. Tesla’s failure to capitalize on his inventions owed a lot to his secretive nature. His habit of announcing discoveries without providing any supporting evidence led many to see him as a crank. He claimed to have received signals from outer space, and to be working on an “egeodynamic oscillator”, whose vibrations would be enough to destroy large buildings. On Tesla’s death in 1943, the FBI confiscated the scientist’s papers, prompting all kinds of speculation about the secret weapons that Tesla may or may not have been working on.

Tesla remains the subject of fascination for Croats and Serbs alike (he is one of the few historical figures whose legacy they share), and Tesla-related museum displays in Zagreb, Belgrade and his home village of Smiljan are becoming ever more popular.

Zagreb's Suburbs

Zagreb’s sightseeing potential is largely exhausted once you’ve covered the compact centre, although there are a few worthwhile trips into the suburbs – all of which are easily accessible by tram or bus. Maksimir, Jarun and Mirogoj cemetery are the park-like expanses to aim for if you want a break from the downtown streets, while the Sava river embankment presents the ideal excuse for a long afternoon stroll. South of the river, the residential high-rise sprawl of Novi Zagreb is home to the city’s coolest cultural attraction – the Museum of Contemporary Art.

Maksimir Park

Three kilometres east of the centre, Maksimir Park is Zagreb’s largest and lushest open space. Named after Archbishop Maximilian Vrhovac, who in 1774 established a small public garden in the southwestern corner of today’s park, Maksimir owes much to his successors Aleksandar Alagović and Juraj Haulik, who imported the idea of the landscaped country park from England. It’s perfect for aimless strolling, with the straight-as-an-arrow, tree-lined avenues at its southwestern end giving way to more densely forested areas in its northern reaches. As well as five lakes, the park is dotted with follies, including a mock Swiss chalet (Švicarska kuća) and a spruced-up belvedere (vidikovac), housing a café which gets mobbed on fine Sunday afternoons. One of Zagreb’s best-equipped children’s play parks can be found here, about five minutes’ walk from the main entrance, just off the main avenue to the left.

The Lauba House

Cloaked in a sheath of matt black on the outside, and boasting a wealth of wrought iron and exposed brickwork within, the expensively restored former cavalry stable and textile factory that is the Lauba House (Kuća Lauba), 4km west of the centre, is Zagreb’s leading private art collection. It’s the brainchild of Tomislav Kličko (the name “lauba” is local dialect in Kličko’s home village for a circle of tree branches), who systematically bought up the works of Croatia’s leading artists at a time when few other individuals were making acquisitions. Unsurprisingly, Kličko ended up with the cream. Occupying centre stage in a regularly rotated collection are the figurative paintings of Lovro Artuković, light installations by Ivana Franke and the glitzy but disturbing sculptures and photographs of Kristian Kožul.

Lake Jarun

On sunny days, city folk head out to Jarun, a 2km-long artificial lake encircled by footpaths and cycling tracks 6km southwest of the centre. Created to coincide with Zagreb’s hosting of the 1987 World Student Games, it’s an important venue for rowing competitions, with a large spectator stand at the western end, although most people come here simply to stroll or sunbathe. The best spot for the latter is Malo jarunsko jezero at Jarun’s eastern end, a bay sheltered from the rest of the lake by a long thin island. Here you’ll find a shingle beach backed by outdoor cafés, several of which remain open until the early hours. This is a good place from which to clamber up onto the dyke that runs along the banks of the River Sava, providing a good vantage point from which to survey the cityscape of Novi Zagreb beyond.

Novi Zagreb

Spread over the plain on the southern side of the River Sava, Novi Zagreb (New Zagreb) is a vast gridiron of housing projects and multilane highways, conceived by ambitious urban planners in the 1960s. The central part of the district is not that bad a place to live: swaths of park help to break up the architectural monotony, and each residential block has a clutch of bars and pizzerias in which to hang out. Outlying areas have far fewer facilities, however, and possess the aura of half-forgotten dormitory settlements on which the rest of Zagreb has turned its back.

The Museum of Contemporary Art

Opened to the public in 2009, the Museum of Contemporary Art (Muzej suvremene umjetnosti) has established itself as the leading art institution in the region. Taking the form of an angular wave on concrete stilts, the Igor Franić-designed building is a deliberate reference to the meandering motif developed by Croatian abstract artist Julije Knifer (1924–2004) and repeated – with minor variations – in almost all of his paintings. The interior is a bit of a meander too, with open-plan exhibition halls and a frequently rotated permanent collection that highlights home-grown movements without presenting them in chronological order. The whole thing demonstrates just how far at the front of the contemporary pack Croatian art always was, although it’s a difficult story for first-time visitors to unravel.

Things you should look out for include the jazzy abstract paintings produced by Exat 51 (a group comprising Vlado Kristl, Ivan Picelj and Aleksandar Srnec) in the 1950s, which show how postwar Croatian artists escaped early from communist cultural dictates and established themselves firmly at the forefront of the avant-garde. Look out too for photos of it’s-all-in-the-name-of-art streakers such as Tomislav Gotovac (1937–2010) and Vlasta Delimar (1956–), who either ran or rode naked through the centre of Zagreb on various occasions, putting Croatia on the international performance-art map in the process. Works by understated iconoclasts Goran Trbuljak, Sanja Iveković and Mladen Stilinović reinforce Croatia’s reputation for the art of the witty, ironic statement. The museum’s international collection takes in Mirosław Bałka’s Eyes of Purification (a mysterious concrete shed outside the front entrance), as well as Carsten Höller’s interactive toboggan tubes. A cinema, concert space and café provide additional reasons to visit.

The Bundek

Novi Zagreb has its own venue for outdoor recreation in the shape of the Bundek, a kidney-shaped lake surrounded by woodland and riverside meadow. Attractively landscaped and bestowed with foot- and cycle-paths, it’s an increasingly popular strolling and picnicking venue. Indeed Bundek is one of the best bets for keeping children entertained, with large, well-equipped children's play parks at either side of the lake. The area is also enormously popular with picnickers at weekends, thanks to the generous supply of light-your-own-fire barbecue stations spread out beneath the trees.

Mount Medvednica

The wooded slopes of Mount Medvednica, or “Bear Mountain”, offer the easiest escape from the city, with the range’s highest peak, Sljeme (1033m), easily accessible on foot or by road. The summit is densely forested and the views from the top are not as impressive as you might expect, but the walking is good and there’s a limited amount of skiing in winter, when you can rent gear from shacks near the top.

Medvedgrad

Commanding a spur of the mountain southwest of the Sljeme summit is the fortress of Medvedgrad. It was built in the mid-thirteenth century at the instigation of Pope Innocent IV in the wake of Tatar attacks, although its defensive capabilities were never really tested and it was abandoned in 1571. Partially reconstructed, the fortress has since the 1990s been home to the Altar of the Homeland (Oltar domovine), an eternal flame surrounded by stone blocks. You can roam the castle’s ramparts, which enjoy panoramic views of Zagreb and the plain beyond.

Sljeme

However you arrive on Sljeme, its main point of reference is the TV transmission tower, built on the summit in 1980. The tower’s top floor originally housed a restaurant and viewing terrace, but the lifts broke down after three months and it’s been closed to the public ever since. A north-facing terrace near the foot of the tower provides good views of the low hills of the Zagorje, a rippling green landscape broken by red-roofed villages. Just west of here is the Tomislavov Dom hotel, home to a couple of cafés and a restaurant, below which you can pick up a trail to the medieval fortress of Medvedgrad (2hr). Alternatively you can follow signs southwest from Tomislavov Dom to the Grafičar mountain hut, some twenty minutes away, where there’s a café serving basic snacks.

Paths continue east along the ridge, emerging after about twenty minutes at the Puntijarka mountain refuge, one of many popular refreshment stops serving the traditional hiker’s fare, grah (bean soup).

Top image: St. Mark's Church in Zagreb © 9MOT/Shutterstock

_listing_1618090225076.jpeg)

_listing_1618089877244.jpeg)